Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. Taken over from the US Air Force by the newly created civilian space agency NASA, it conducted twenty uncrewed developmental flights (some using animals), and six successful flights by astronauts. The astronauts were collectively known as the “Mercury Seven”, and each spacecraft was given a name ending with a “7” by its pilot.

The Space Race began with the 1957 launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1. This came as a shock to the American public, and led to the creation of NASA to expedite existing US space exploration efforts, and place most of them under civilian control. After the successful launch of the Explorer 1 satellite in 1958, crewed spaceflight became the next goal. The Soviet Union put the first human, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, into a single orbit aboard Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. Shortly after this, on May 5, the US launched its first astronaut, Alan Shepard, on a suborbital flight. Soviet Gherman Titov followed with a day-long orbital flight in August 1961. The US reached its orbital goal on February 20, 1962, when John Glenn made three orbits around the Earth. When Mercury ended in May 1963, both nations had sent six people into space, but the Soviets led the US in total time spent in space.

The Mercury space capsule was produced by McDonnell Aircraft, and carried supplies of water, food and oxygen for about one day in a pressurized cabin. Mercury flights were launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, on launch vehicles modified from the Redstone and Atlas D missiles. The capsule was fitted with a launch escape rocket to carry it safely away from the launch vehicle in case of a failure. The flight was designed to be controlled from the ground via the Manned Space Flight Network, a system of tracking and communications stations; back-up controls were outfitted on board. Small retrorockets were used to bring the spacecraft out of its orbit, after which an ablative heat shield protected it from the heat of atmospheric reentry. Finally, a parachute slowed the craft for a water landing. Both astronaut and capsule were recovered by helicopters deployed from a US Navy ship.

The Mercury project gained popularity, and its missions were followed by millions on radio and TV around the world. Its success laid the groundwork for Project Gemini, which carried two astronauts in each capsule and perfected space docking maneuvers essential for crewed lunar landings in the subsequent Apollo program announced a few weeks after the first crewed Mercury flight.

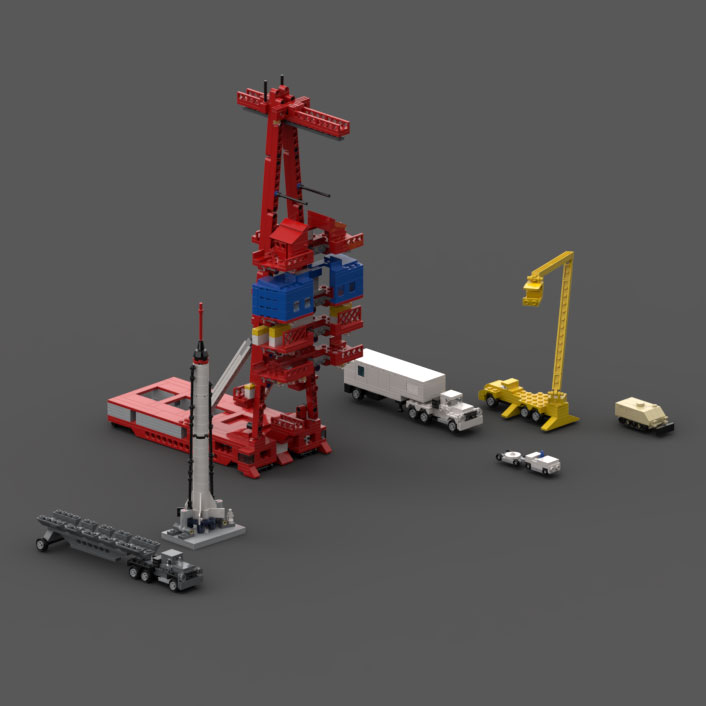

Launch escape system testing

A 55-foot-long (17 m) launch vehicle called Little Joe was used for uncrewed tests of the launch escape system, using a Mercury capsule with an escape tower mounted on it. Its main purpose was to test the system at max q, when aerodynamic forces against the spacecraft peaked, making separation of the launch vehicle and spacecraft most difficult. It was also the point at which the astronaut was subjected to the heaviest vibrations. The Little Joe rocket used solid-fuel propellant and was originally designed in 1958 by NACA for suborbital crewed flights, but was redesigned for Project Mercury to simulate an Atlas-D launch. It was produced by North American Aviation. It was not able to change direction; instead its flight depended on the angle from which it was launched. Its maximum altitude was 100 mi (160 km) fully loaded. A Scout launch vehicle was used for a single flight intended to evaluate the tracking network; however, it failed and was destroyed from the ground shortly after launch.

Beach Abort

Beach Abort

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Little Joe I

Little Joe I

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Suborbital flight

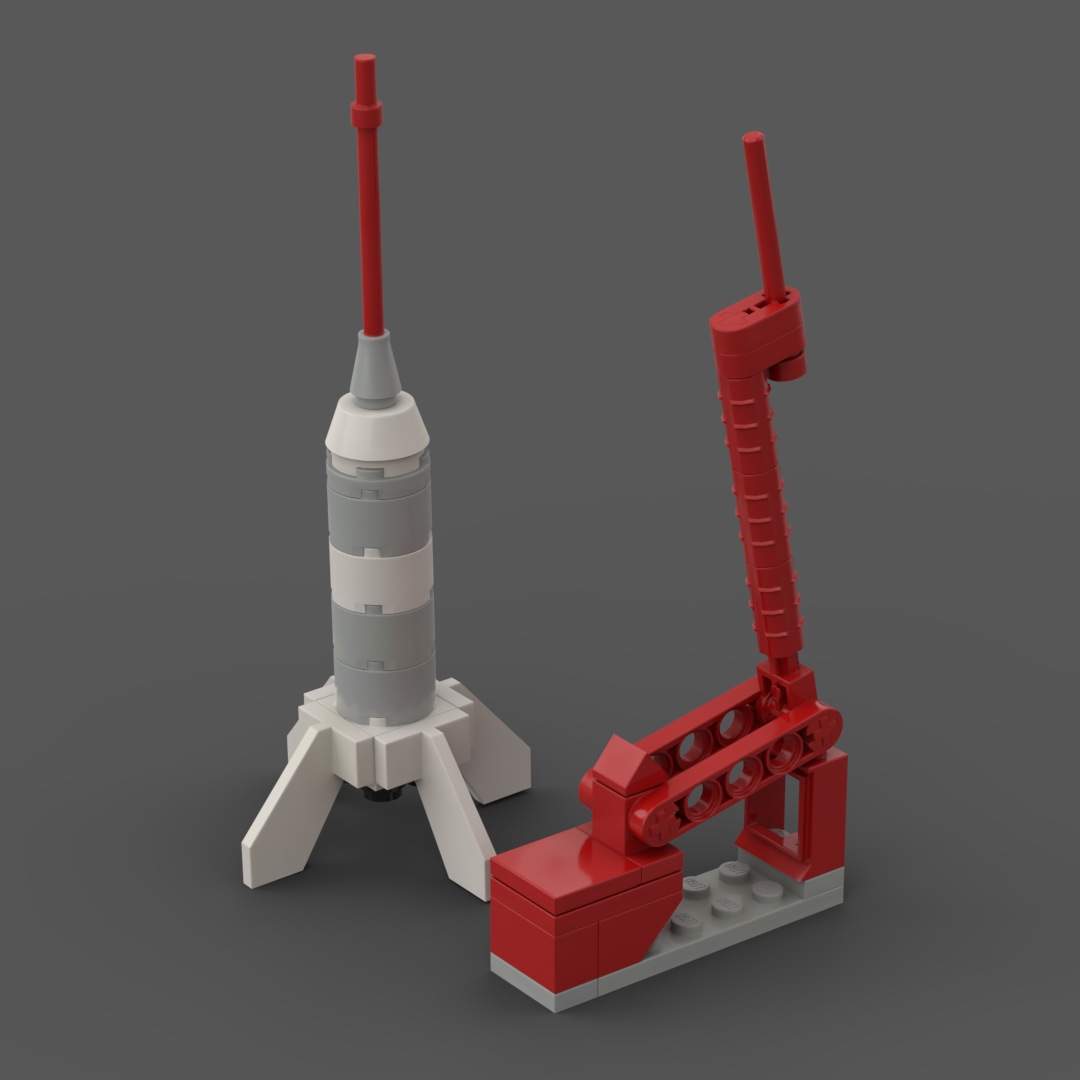

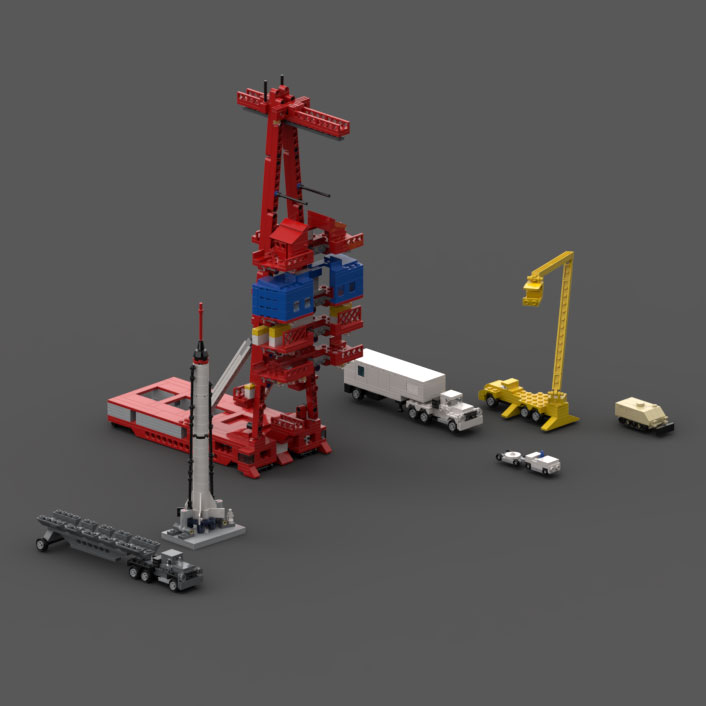

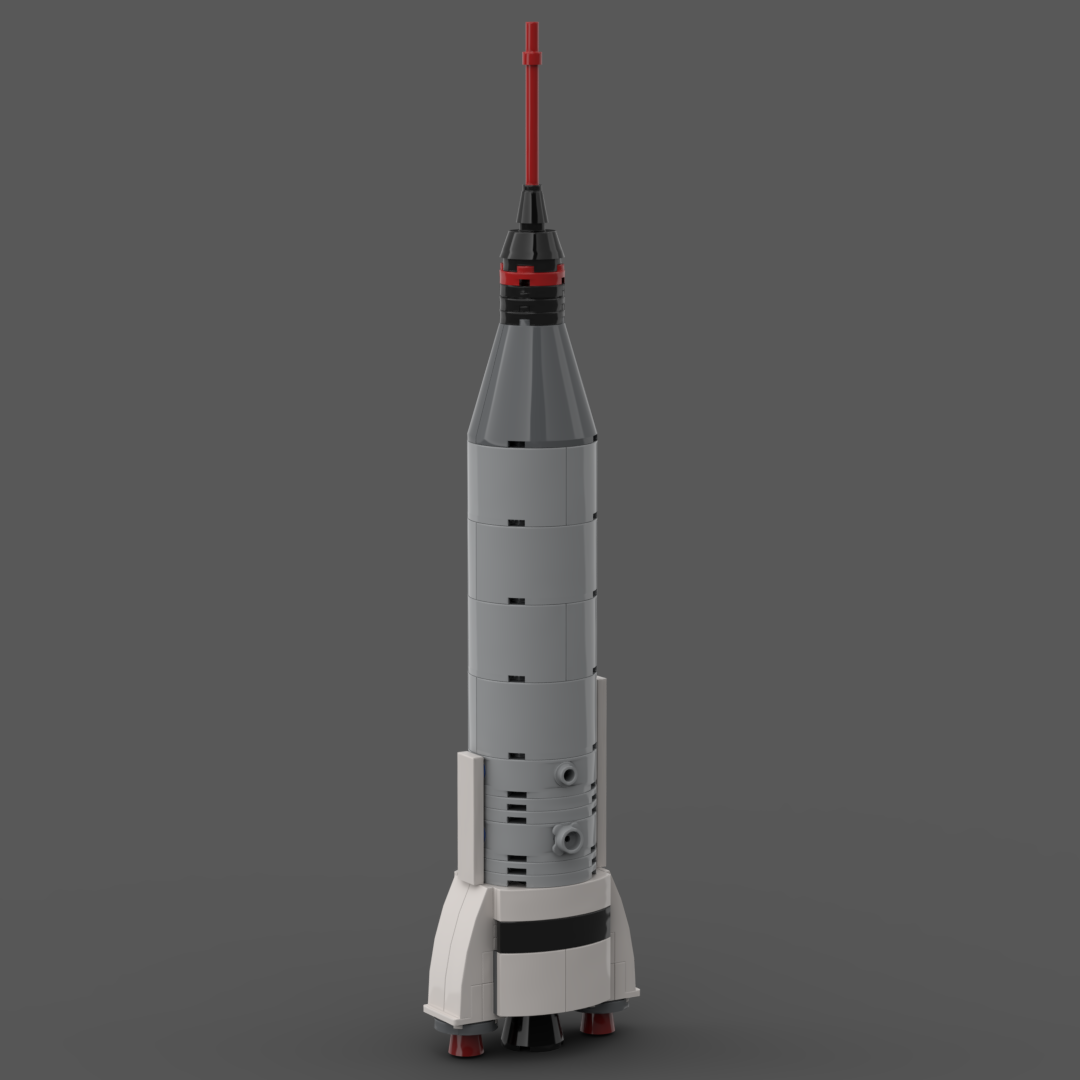

The Mercury-Redstone Launch Vehicle was an 83-foot-tall (25 m) (with capsule and escape system) single-stage launch vehicle used for suborbital (ballistic) flights.It had a liquid-fueled engine that burned alcohol and liquid oxygen producing about 75,000 pounds-force (330 kN) of thrust, which was not enough for orbital missions. It was a descendant of the German V-2, and developed for the U.S. Army during the early 1950s. It was modified for Project Mercury by removing the warhead and adding a collar for supporting the spacecraft together with material for damping vibrations during launch. Its rocket motor was produced by North American Aviation and its direction could be altered during flight by its fins. They worked in two ways: by directing the air around them, or by directing the thrust by their inner parts (or both at the same time). Both the Atlas-D and Redstone launch vehicles contained an automatic abort sensing system which allowed them to abort a launch by firing the launch escape system if something went wrong. The Jupiter rocket, also developed by Von Braun’s team at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, was considered as well for intermediate Mercury suborbital flights at a higher speed and altitude than Redstone, but this plan was dropped when it turned out that man-rating Jupiter for the Mercury program would actually cost more than flying an Atlas due to economics of scale. Jupiter’s only use other than as a missile system was for the short-lived Juno II launch vehicle, and keeping a full staff of technical personnel around solely to fly a few Mercury capsules would result in excessively high costs.

Mercury Redstone set

Mercury Redstone set

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Launch Complex 5

Launch Complex 5

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Mercury-Redstone

Mercury-Redstone

1st launch attempt: 21 November 1960

Launch Site: Cape Canaveral, Florida

Orbital Type: Sub-Orbital

Country of Origin: United States

Orbital flight

Orbital missions required use of the Atlas LV-3B, a man-rated version of the Atlas D which was originally developed as the United States’ first operational intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by Convair for the Air Force during the mid-1950s. The Atlas was a “one-and-one-half-stage” rocket fueled by kerosene and liquid oxygen (LOX).The rocket by itself stood 67 feet (20 m) high; total height of the Atlas-Mercury space vehicle at launch was 95 feet (29 m).

The Atlas first stage was a booster skirt with two engines burning liquid fuel. This, together with the larger sustainer second stage, gave it sufficient power to launch a Mercury spacecraft into orbit. Both stages fired from lift-off with the thrust from the second stage sustainer engine passing through an opening in the first stage. After separation from the first stage, the sustainer stage continued alone. The sustainer also steered the rocket by thrusters guided by gyroscopes. Smaller vernier rockets were added on its sides for precise control of maneuvers.

Mercury Atlas LV-3B

Mercury Atlas LV-3B

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Big Joe 1 – Atlas LV-3B

Big Joe 1 – Atlas LV-3B

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Launch Complex 14

Launch Complex 14

1st launch attempt:

Launch Site:

Orbital Type:

Country of Origin:

Atlas D (Mercury)

Atlas D (Mercury)

1st launch attempt: 9 September 1959

Launch Site: Cape Canaveral, Florida

Orbital Type: Orbital

Country of Origin: United States

Astronauts

NASA announced the following seven astronauts – known as the Mercury Seven – on April 9, 1959: M. Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper

John H. Glenn, Jr., Virgil I. Grissom, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr. and Donald K. Slayton.

Shepard became the first American in space by making a suborbital flight in May 1961. He went on to fly in the Apollo program and became the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Gus Grissom, who became the second American in space, also participated in the Gemini and Apollo programs, but died in January 1967 during a pre-launch test for Apollo 1. Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in February 1962, then quit NASA and went into politics, serving as a US Senator from 1974 to 1999, and returned to space in 1998 as a Payload Specialist aboard STS-95. Deke Slayton was grounded in 1962, but remained with NASA and was appointed Chief Astronaut at the beginning of Project Gemini. He remained in the position of senior astronaut, in charge of space crew flight assignments among many other responsibilities, until towards the end of Project Apollo, when he resigned and began training to fly on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975, which he successfully did. Gordon Cooper became the last to fly in Mercury and made its longest flight, and also flew a Gemini mission. Carpenter’s Mercury flight was his only trip into space. Schirra flew the third orbital Mercury mission, and then flew a Gemini mission. Three years later, he commanded the first crewed Apollo mission, becoming the only person to fly in all three of those programs.

One of the astronauts’ tasks was publicity; they gave interviews to the press and visited project manufacturing facilities to speak with those who worked on Project Mercury. To make their travels easier, they requested and got jet fighters for personal use. The press was especially fond of John Glenn, who was considered the best speaker of the seven. They sold their personal stories to Life magazine which portrayed them as ‘patriotic, God-fearing family men.’ Life was also allowed to be at home with the families while the astronauts were in space. During the project, Grissom, Carpenter, Cooper, Schirra and Slayton stayed with their families at or near Langley Air Force Base; Glenn lived at the base and visited his family in Washington DC on weekends. Shepard lived with his family at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia.

Other than Grissom, who was killed in the 1967 Apollo 1 fire, the other six survived past retirement and died between 1993 and 2016.

Crewed

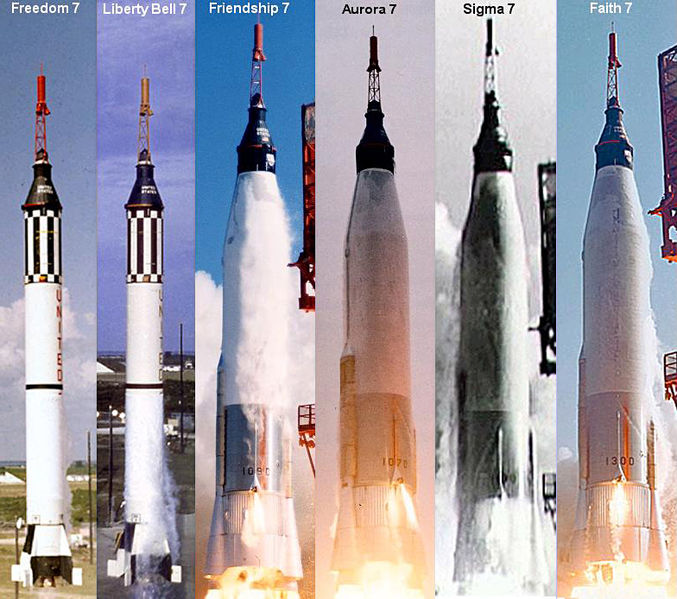

All of the six crewed Mercury flights were successful, though some planned flights were canceled during the project. The main medical problems encountered were simple personal hygiene, and post-flight symptoms of low blood pressure. The launch vehicles had been tested through uncrewed flights, therefore the numbering of crewed missions did not start with 1. Also, there were two separately numbered series: MR for “Mercury-Redstone” (suborbital flights), and MA for “Mercury-Atlas” (orbital flights). These names were not popularly used, since the astronauts followed a pilot tradition, each giving their spacecraft a name. They selected names ending with a “7” to commemorate the seven astronauts.

| Mission | Call-sign | Pilot | Launch | Site | Duration | Orbits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR-3 | Freedom 7 | Shepard | 14:34 on May 5, 1961 | LC-5 | 15m 22s | 0 |

| MR-4 | Liberty Bell 7 | Grissom | 12:20 on Jul. 21, 1961 | LC-5 | 15m 37s | 0 |

| MA-6 | Friendship 7 | Glenn | 14:47 on Feb. 20, 1962 | LC-14 | 4h 55m 23s | 3 |

| MA-7 | Aurora 7 | Carpenter | 12:45 on May 24, 1962 | LC-14 | 4h 56m 5s | 3 |

| MA-8 | Sigma 7 | Schirra | 12:15 on Oct. 3, 1962 | LC-14 | 9h 13m 15s | 6 |

| MA-9 | Faith 7 | Cooper | 13:04 on May 15, 1963 | LC-14 | 1d 10h 19m 49s | 22 |

Uncrewed

The 20 uncrewed flights used Little Joe, Redstone, and Atlas launch vehicles. They were used to develop the launch vehicles, launch escape system, spacecraft and tracking network. One flight of a Scout rocket attempted to launch a satellite for testing the ground tracking network, but failed to reach orbit. The Little Joe program used seven airframes for eight flights, of which three were successful. The second Little Joe flight was named Little Joe 6, because it was inserted into the program after the first 5 airframes had been allocated.

| Mission | Launch | Duration | Purpose | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Joe 1 | August 21, 1959 | 20s | Test of launch escape system during flight. | Failure |

| Big Joe 1 | September 9, 1959 | 13m 00s | Test of heat shield and Atlas/spacecraft interface. | Partial success |

| Little Joe 6 | October 4, 1959 | 5m 10s | Test of spacecraft aerodynamics and integrity. | Partial success |

| Little Joe 1A | November 4, 1959 | 8m 11s | Test of launch escape system during flight with boiler plate capsule. | Partial success |

| Little Joe 2 | December 4, 1959 | 11m 6s | Escape system test with primate at high altitude. | Success |

| Little Joe 1B | January 21, 1960 | 8m 35s | Maximum-q abort and escape test with primate with boiler plate capsule. | Success |

| Beach Abort | May 9, 1960 | 1m 31s | Test of the off-the-pad abort system. | Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 1 | July 29, 1960 | 3m 18s | Test of spacecraft / Atlas combination. | Failure |

| Little Joe 5 | November 8, 1960 | 2m 22s | First test of escape system with a production spacecraft. | Failure |

| Mercury-Redstone 1 | November 21, 1960 | 2s | Test of production spacecraft at max-q. | Failure |

| Mercury-Redstone 1A | December 19, 1960 | 15m 45s | Qualification of spacecraft / Redstone combination. | Success |

| Mercury-Redstone 2 | January 31, 1961 | 16m 39s | Qualification of spacecraft with chimpanzee named Ham. | Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 2 | February 21, 1961 | 17m 56s | Qualified Mercury/Atlas interface. | Success |

| Little Joe 5A | March 18, 1961 | 23m 48s | Second test of escape system with a production Mercury spacecraft. | Partial success |

| Mercury-Redstone BD | March 24, 1961 | 8m 23s | Final Redstone test flight. | Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 3 | April 25, 1961 | 7 m 19 s | Orbital flight with robot astronaut. | Failure |

| Little Joe 5B | April 28, 1961 | 5m 25s | Third test of escape system with a production spacecraft. | Success |

| Mercury-Atlas 4 | September 13, 1961 | 1h 49m 20s | Test of environmental control system with robot astronaut in orbit. | Success |

| Mercury-Scout 1 | November 1, 1961 | 44s | Test of Mercury tracking network. | Failure |

| Mercury-Atlas 5 | November 29, 1961 | 3h 20m 59s | Test of environmental control system in orbit with chimpanzee named Enos. | Success |